From idea to live in 15 minutes

I just built a complete campaign website in 15 minutes.

Started with an idea about procrastination and 5-minute commitments. Did deep research with Claude on the psychology and statistics. Then researched what people actually say about procrastination on forums and Reddit.

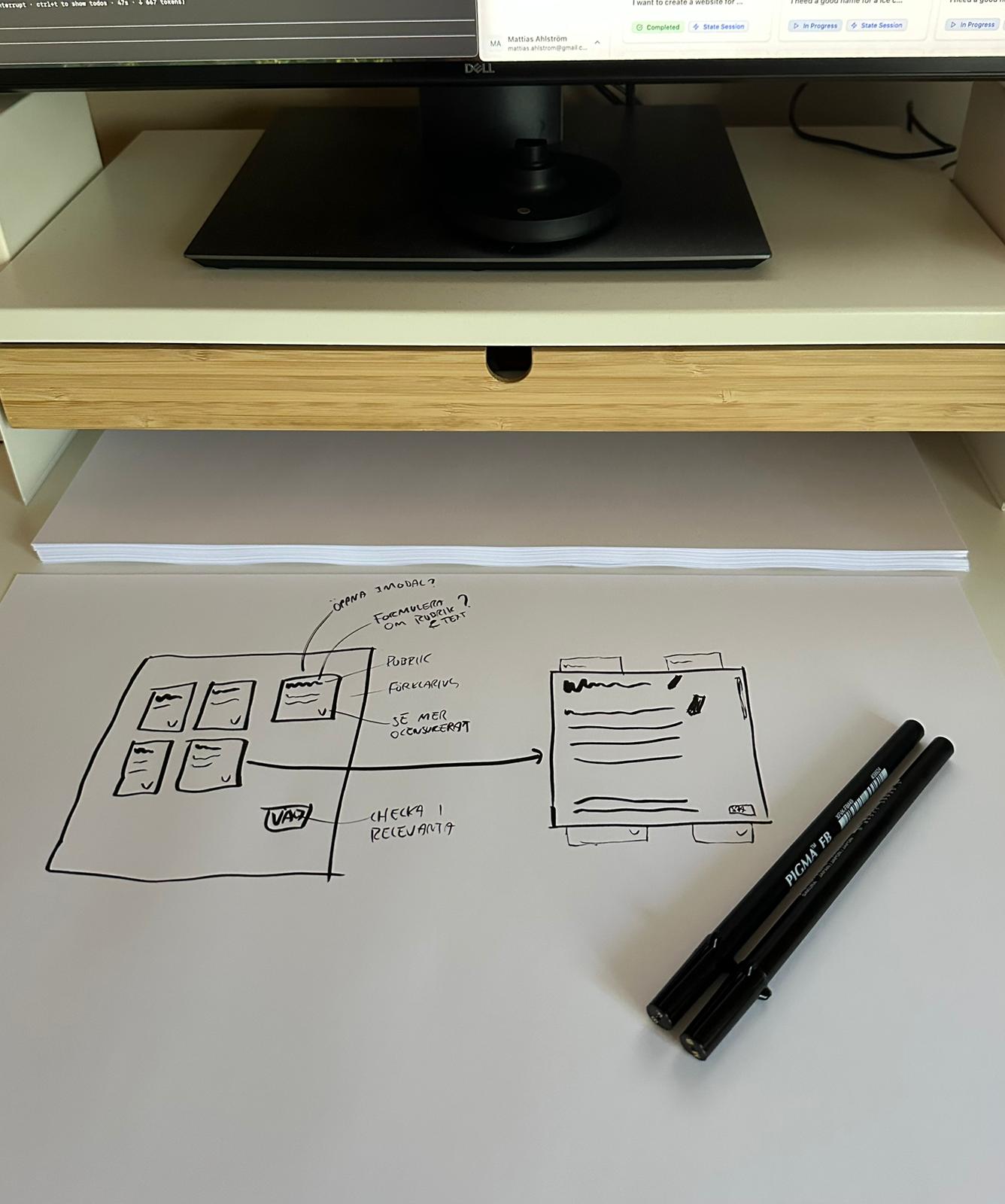

Opened Claude Code, gave it browser access, pointed it to Pexels for background images. Asked for a compelling site with scroll-snap and the best arguments from my research.

15 minutes later: a polished campaign site that would normally take weeks.

Total cost: $5 Cloudflare hosting, $15 domain, $90 Claude subscription.

Here’s what this means for the industry:

The gap isn’t between AI and humans. It’s between people who can write prompts and people who can launch websites.

Knowing how to use ChatGPT is common. Knowing how to take AI output and make it live on the internet is rare.

Small agencies are caught in the middle. They can’t compete with big shops on reputation or with AI-assisted individuals on speed and price.

The winners will be the few people who combine AI skills with web development knowledge. They’ll serve businesses that want custom work without enterprise timelines or budgets.

Most traditional small agencies won’t make this transition. Not because AI will replace them, but because very few people can bridge the gap between AI conversations and working websites.